LE MEURICE – Alain Ducasse: New French Haute Cuisine for the 21st Century, A

@Bob Peterson for Hungry for Paris With its lavish ormolu moldings and grand crystal chandeliers, Le Meurice is one of the most beautiful dining rooms in Paris. For all of its rococo splendor, however, the special affection I have for this space runs back to a soft Indian summer morning fourteen years ago when I came to have a tour of the hotel while it was undergoing renovations. I entered through a side door in the construction hoardings, and looking for the woman with whom I had an appointment, I found myself on the edge of the dining room, where a team of men in dusty blue overalls was arguing in Italian.

@Bob Peterson for Hungry for Paris With its lavish ormolu moldings and grand crystal chandeliers, Le Meurice is one of the most beautiful dining rooms in Paris. For all of its rococo splendor, however, the special affection I have for this space runs back to a soft Indian summer morning fourteen years ago when I came to have a tour of the hotel while it was undergoing renovations. I entered through a side door in the construction hoardings, and looking for the woman with whom I had an appointment, I found myself on the edge of the dining room, where a team of men in dusty blue overalls was arguing in Italian.

“No, no, that’s not the right color. That’s cream, not almond,” an older man said to his colleague as they stared at a tiny piece of stone down on their knees on the mosaic floor they were creating. “The almond is too dark, the cream would be better. This is a corner of the room and the light in Paris is so often gray,” said his colleague. They changed it back and forth several times, and finally settled on the cream. I’d never seen such a large and elaborate mosaic being created before, and I never enter this room without remembering their pride and their seriousness.

Roasted figs with creme fraiche

Roasted figs with creme fraiche

So a passionate attention to detail really does underlie the experience of a meal at one of the most legendary dining rooms in Paris, and this is why I was so curious to go to dinner the other night. Chef Yannick Alleno, who presided at Le Meurice for many years and won three stars there, moved on during the winter of 2013, and now the restaurant has joined the stable of tables run by Alain Ducasse, who placed Christophe Saintagne from Restaurant Alain Ducasse at the Hotel Plaza Athenee, a sister property to Le Meurice, since they’re both part of the Dorchester Group, in the kitchen now that this latter hotel is about to be renovated.

Waiting for Bruno in the street, I couldn’t help but wondering if the impending meal might feel like finding a different bird in the nest another one had built. Then Bruno showed up in his Mini convertible, and it was amusing to watch the top-hatted valet park this nice little car between a Bentley and a Lamborghini. When we went inside and were ushered through the discrete door behind a panel in the lobby, the dining room was not only every bit as magnificent as I remembered but also pleasantly more subdued. Several years ago, designer Philippe Starck had tinkered with the original post-renovation décor, and since I don’t want irony-inflected wit to move the sort of double-barreled grandeur I experience so rarely off-center, I’d never really taken to his tweaks.

Alain Ducasse is both extremely discreet and a real aesthete in the best sense of this word, so it was fascinating to register the subtle but powerful changes he’d made at the restaurant just a few weeks after it became one of his. The only ornament on our ecru linen dressed table was a plump ripe yellow tomato on a small smooth shake of timber (we later learned it came from one of the many trees felled in the forests of Versailles during a terrible storm several years ago), and it was a pregnant clue as to the visual and gastronomic sensibility of the meal that followed.

The first dish to arrive at the table was a small square sandwich of toasted country bread filled with fleshy pleasantly feral tasting cepes and a veil of smoked country ham. At the same time it appeared a waiter brought the salt and pepper in a series of gray porcelain cubes that briefly grabbed my attention with their stark beauty before I was distracted by the arrival of our first course, a black cast-iron casserole. When the lid was removed, we saw a small pretty still-life of vegetables that had been cooked on a bed of gray sea salt, and the waiter then supplied us with long thin forks to spear them with and dip into a tart green herbed dairy sauce. The vegetables—carrots, potatoes, onions, baby leeks—were homey and satisfying, and the gently astringent sauce cleansed the palate for everything to come. This communal dish also whispered that the pleasures of the table are often best shared. As much as this opener surprised us, we were both transfixed by the plate and the small fragile ramekin the sauce came in. “It must be him,” said Bruno, but we couldn’t gracefully upend anything to check until a few minutes later when we saw Belgian ceramicist Pieter Stockman’s named printed on their bottoms.

We’d first discovered Stockman’s exquisite ceramics in a boutique in Antwerp, and I’d later seen them at Restaurant Jean-Francois Piege in Paris. What transfixed me, though, was deciphering what these very carefully objects were saying. What I surmised is that in the 21st century, luxury should pure and delicate, or a series of simple evanescent pleasures that are humble and healthy rather than ostentatious and self-indulgent. Clearly Ducasse had decided to make Le Meurice his laboratory for reinventing French haute cuisine for the 21st century.

This extended to the deeply considered casting of the staff in this dining room, where I happily saw more women working than I ever had before in such an exalted restaurant. Among them, the charming and enviously polyglot Spanish woman who explained the haiku-like menu to us, and then the sommelier, Estelle Touzet, whose love and knowledge of wine and eloquent and thought-provoking way of describing it became one of the major threads of pleasure that animated our evening.

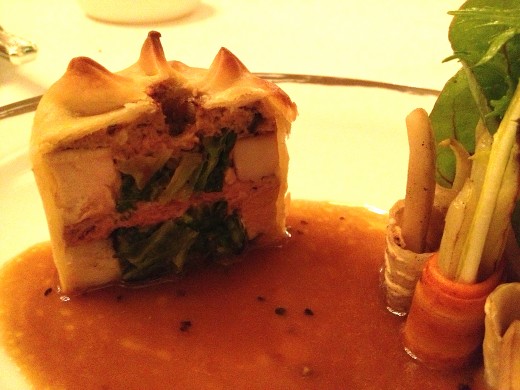

Bruno loved his sautéed autumn fruit and vegetables served with a deglazed sauce of cooking juices and cider vinegar—a varying palate of acidities and different shades of bitterness is another recurring element of this kitchen, while my pate chaud de pintade au chou came as an elegantly fragile cartridge of pastry filled with chunks of tender guinea hen and Savoy cabbage bound by a baked mousse of liver and gizzards.

The nearly nude way in which our fish courses were prepared further emphasized the angelic intentions of the kitchen. A magnificent lozenge of butter-basted turbot came on an identically sized piece of fine toast lightly spread with tapenade, all that was needed to emphasize its natural flavor with the foil of a little salt and texture. It reminded me of the innocent simplicity with which fish is often cooked in Scandinavia, while John Dory, also cooked on the bone, was presented on laser-fine slices of fig with coin-sized pieces of turnip and a salad of herbs. Here, the fine graininess of the fig seeds flattered the fish, while the gentle bitterness of the turnips punctuated its natural sweetness.

Main courses were even more plain-spoken in an almost Amish sort of way. Bruno’s colvert (wild duck) was cooked rare and garnished with halved black grapes, kernels of corn and a luscious salamis (the bird’s bones pounded to a smooth paste with red wine and stock), while my veal sweetbreads surprised me even after the detailed explanation of this preparation I’d been given at the beginning of the meal. A perfectly round slice of sweetbread was topped with a fine crust of toasted golden bread crumbs and came with a comma-shaped side dish of roasted heirloom tomatoes with a few melted shards of Parmesan. Restraint was the clear intention of this preparation, with the tomatoes intended to provide an acidic foil to the rich creamy flavor and texture of the sweetbreads. Since I love sweetbreads, this was the one moment in the meal when I yearned for a bit more, but in terms of the logic behind my menu, it was impeccable.

Ducasse is now producing superb chocolate at an atelier in Paris near the Bastille, and it supplied the raw materials for a stunningly good finale—chocolate ice cream decorated with fine broken panes of caramel on a bed of almonds and an accessorizing cocoa mousse and a pitcher of hot chocolate. Following the waiter’s instructions, I spooned up some of the mousse and ice cream with a nut or two and dribbled it with melted chocolate before experiencing an avalanche of pleasure that was propelled into even higher relief by the deceptively modest tone of the proceeding meal. The glass of ten-year-old Barbeito Bual Old Reserve Madeira, which sommelier Touzet explained she’d chosen for the faint flavor of the salt in the island’s soil expressed through the grapes behind the foreground tastes of caramel, leather and tobacco, added a deeper glow of sensuality to this shudderingly good concoction. Bruno enjoyed his roasted figs, which were served in a fragile bowl of mesmerizingly aromatic dried fig leaves with a granite of red wine atop a hazelnut cream, and we were more relieved than surprised when the traditional trolley of post-prandial sweetmeats was brought tableside and contained freshly made fruit compotes and sorbets instead of the usual mignardaises, candies and pastries. This gentle and planed down proposal was much more in keeping with the prevailing—and even invigorating—theme of restraint that had informed our meal than a selection of sugary little cakes would have been.

There was nothing ascetic or puritanical about the moderation that was the rudder of this meal, however. Instead it recognized that many people coming to a restaurant of this caliber today are there to be entertained as much as they are to be fed, and that almost anyone who can afford such an experience probably leads a life of habitual abundance.

Ultimately, this was a superb and very daring meal, because after making his reputation with an

exactingly disciplined take on the simple but naturally baroque character of European Mediterranean cooking, Ducasse has completely revised and reinvented his repertoire. What he instinctively understands, you see, is that as the conventional summit of the French culinary experience, haute cuisine has always been a mirror of our aspirations, pleasures, and even fears, and in his stunningly astute reading of these evolving codes in a still emerging new century, he’s come up with an intriguing new recipe for pleasure. Gallic gastronomic luxury should be simple and wholesome.

Restaurant Le Meurice – Alain Ducasse, Hotel Le Meurice, 228 rue de Rivoli, 1st, Tel. 01-44-58-10-55,

Metro: Concorde or Tuileries. Open Monday to Friday for lunch and dinner. Closed Saturday and Sunday.

Average a la carte 235 Euros, Five-course tasting menu 380 Euros. www.lemeurice.com/le-meurice-restaurant