3 Things I Like A Lot: La Bédigue, La Cuisine Francaise, Tava Hada Pilpelta

Since the restaurants that are normally my main subject here are currently closed in France, food has taken on a different dimension in my life. Instead of dining out four or five times a week, now I’m the one who’s doing cooking. And although I’ve always loved to cook, I find myself in a constant search for new tastes, recipes and inspiration in the kitchen. So I’ve decided to start a new column here called 3 THINGS I LIKE A LOT, which will cover foods, cookbooks, books, wine, and all of my other latest discoveries and enthusiasms.

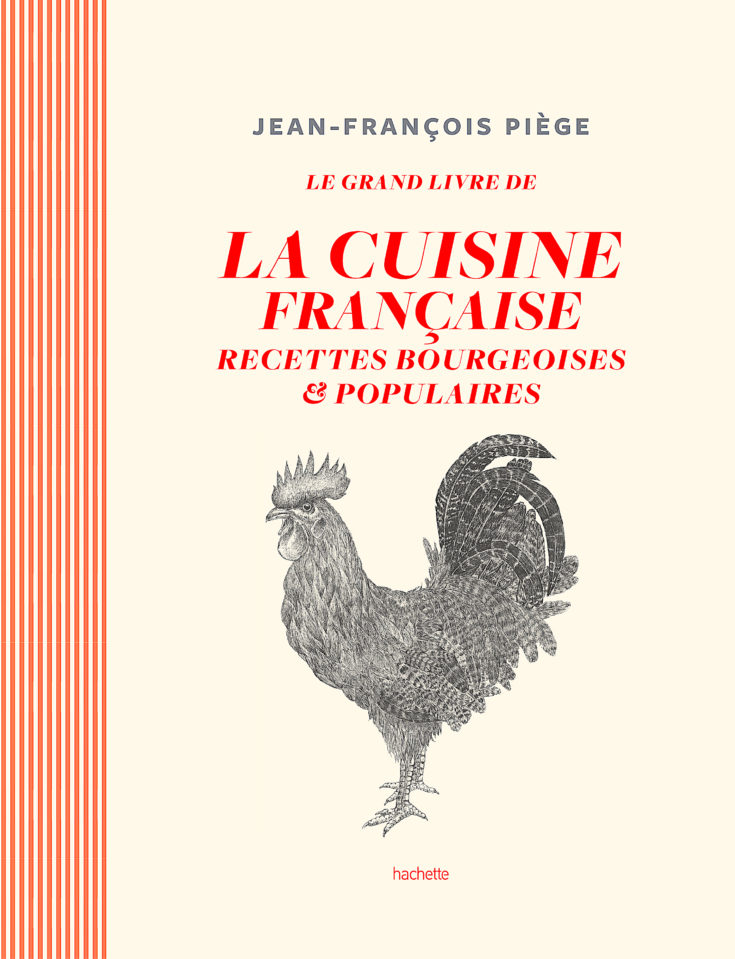

For this first column, I begin with La Bédigue, a newly invented French cheese; La Cuisine Francaise, Jean-Francois Piege’s new cookbook (in French only); and the superb harissa and other condiments that Marseillais producer William Lellouche is producing as part of his Tava Hada Pilpelta collection of high-quality kitchen helpers.

Nestled in a little pine box, La Bédigue is the work of Nimes fromager Sylvain Cregut, who wanted to create a cheese that’s a reflection of the terroir of Le Gard, the mostly rural southern French departement of which he is a native. It’s a soft ewe’s milk cheese produced on a farm in the countryside between Nimes and Uzes, and its texture presents compact but pleasantly perceptible curds. Cregut ages it with Cartagène, a Languedoc wine made from freshly pressed grape juice (80%) and eau-de-vie du vin (20%), which gives it a subtle ambered floral scent and a very faint viniferousness on the palate. I find it to be a perfect dessert cheese served with dried fruit and almonds and expect it will also be great as a picnic cheese this summer.

For now, the only place you can find this treat is at Sylvain Cregut’s stall in Les Halles de Nimes, the city’s covered market, which is open daily. Les Fromages de Sylvain, Allée du Curry (all of the aisles in Les Halles de Nimes are named after herbs or spices), 5 rue des Halles, Nimes.

As time passes, I have become more and more exigent about the cookbooks that actually live in my kitchen and not on the shelves in my office. The ones that join me in the kitchen are the ones that I use most often for reference and cook from regularly. The latest addition to this little stable is chef Jean-François Piège’s outstanding new cookbook with beautiful drawings by Michel Tavares and many luscious photographs.

With five restaurants in Paris, including Le Grand Restaurant, L’Epi d’Or, Clover Grill, Clover Green and La Poule au Pot, Piège has long been one of my very favorite French chefs for the fact that his intense technical skills are unfailingly at the service of his nimble, witty and intelligently original gastronomic imagination. The other reason is that both of us are besotted with La Cuisine Bourgeoise, or those grand traditional recipes of the French kitchen like veal Prince Orloff or, more humbly but no less deliciously, stuffed cabbage.

There are recipes for both in this wonderful tome, along with a whole alphabet or sauces, classics, and desserts, many of which have names that resonate of the great names of 19th and 20th century French literature. When I read Madame Bovary as a fifteen year old boy in a Connecticut suburb, I was as fascinated by the occasional reference to food as I was to accelerating inevitability and exquisitely rendered doom of the poor woman for whom the novel is named.

Piège has always loved the great French gastronome Auguste Escoffier as much as I have, too, so I couldn’t wait to read this thumping but unexpectedly agile book with some thousand recipes when it arrived at the beginning of December 2020. And I did read it, from cover to cover, because it is so well-written, charming and consistently informative.

Mind you, some of these recipes require some real time and work in the kitchen, so this might not be a book for the rustle-up-dinner-on-a-sheet-pan crowd, but everything I’ve cooked from this book, including his recipe for sole meunière and the first, and possibly only, terrine de lapin en gelée (rabbit terrine) I’ve ever made was staggeringly delicious.

French language edition only, Hachette Cuisine, 60 Euros.

Like many people right now, I’m more dependent on good condiments than ever before. This is because I don’t always have time to cook dishes that build layers of flavor from the ground up, like a good daube de boeuf provencal, for example, a recipe I’ve been making every other week this winter. So what I’ve been needing lately are really good quality condiments that can do this work for me, like the superb artisan harissa and other foods made by William Lellouche in his atelier in Marseille and sold under the Tava Hada Pilpelta label.

I’ve loved harissa ever since the first time I tasted it on a trip to Tunisia in 1989. In the inexpensive restaurants which I preferred to the dreary buffet of the beach hotel we were were staying at on the island of Djerba, there was a little glass pot of it in the middle of every Formica topped table next to a U shaped chromed stand filled with paper napkins so flimsy you had to use half the rack to actually wipe your fingers or your mouth clean. Experimenting with tiny spoonfuls, it was delicious on everything we ordered, brik (flaky pastry) filled with tuna, hard-cooked egg, sweet potatoes or some combination of all of them, grilled merguez, and, eventually, stirred into a ladle of the broth of a good couscous as the proprietor of a tiny little restaurant in the countryside showed us how to do.

So in a souk before returning to Paris, I bought two little plastic tubs of harissa and tucked them into my suitcase inside of plastic bags. I think you know what finally happened. My clothing looked like I been involved in some kind of hot-pepper serial killing when I unzipped my bag at home that night. I wish I could say that this first lesson in the perils of transporting foods in checked bags taught me the error of my ways. But it didn’t.

Five years later, I swathed a beautiful bottle of olive oil given to me by a Croatian farmer inside a huge lozenge of plastic bags and bubble wrap and then enclosed this wad inside of several polo shirts in the middle of my suitcase before I flew from Split to Zagreb, where I was staying at the Esplanade, a very elegant hotel in the Croatian capital.

This is why I’d put on my last clean ironed linen shirt that morning in anticipation of the occasion of my arrival. On a sleepy Sunday afternoon in August when Zagreb was almost empty, I was received with a glare from the leonine man at the front desk, which I assumed I’d earned for pulling my own roller bag across the glossy stone floor of the lobby behind me instead of waiting for a porter. In any event, I gave him my name and handed over my passport and credit card, which he dropped on the blotter in front of him like they might be carrying the plague. Then he raised his eyebrows and spoke.

“Sir, You’re dripping,” he said.

I was embarrassed even before I knew exactly what he meant. Was he referring to perspiration? If so, he was wrong. I was dry as a bone. One way or another, it was a very rude remark. Then he said it again, this time with a sharp nod at something over my shoulder.

“Sir, You’re dripping.” I blushed and looked around the lobby panicked, and finally my eyes fell upon the very pretty golden-green puddle of oil sluicing onto the floor around the wheels of my bag.

I keep the shudderingly ugly daisy-print shirt that was the only thing the men’s shop across the street from the hotel had in my size when I went out to buy a change of clothing the following morning after sending the oil-soaked contents of my bag to the hotel laundry hanging in my closet as a sort of permanent reminder not to make the same mistake again. But suffice it to say some lessons are just never learned, especially when pleasure is involved.

I know, for example, that the next time I can travel to the U.S., I will definitely be returning to France with a bottle or two of the same Robert Rothschild Farm Roasted Pineapple and Habanero sauce that my sister sent me for Christmas, because it does such great things for pork and poultry.

In any event, today you can actually avoid catastrophic dry-cleaning bills if you want Tunisian harissa, because they sell it at Trader Joe’s. But as is obviously true of every condiment, it’s the quality of the ingredients that determine the pleasure delivered by the final product. And if Trader Joe’s is pretty good, it’s just nowhere near being in the same league as Tava Hada Pilpelta.

I first came across William Lellouche’s harissa on the site of the excellent grocery-delivery company La Belle Vie, which began in Paris but now services all of France and just gets better every single day.

Since I’m a sucker for condiments under any circumstance, I popped a jar in my order and had sort of forgotten about it until I found the little pot at the bottom of one of the sturdy brown paper bags La Belle Vie admirably uses instead of anything plastic. I tasted it when I went to make a vinaigrette for the steamed chicken we had with a steam broccoli-and-avocado salad for dinner that night and it was so good I actually put another little dribble on a piece of baguette just to taste it again (a half-teaspoon in the olive-oil-and-lemon-juice vinaigrette I spooned over the chicken brought just the resonance and raciness I was looking for, too; and if I’d been making this vinaigrette for myself, I’d have used a whole teaspoon, but there’s on ongoing battle between me and Bruno in this household over what spicy means. Suffice it to say that his spiciness is French timid, and mine to him is American insanity).

What made Tava Hada Pilpelta harissa so different from grocery store or corner shop harissa is that it was incredibly fresh and had a beautiful texture that drove me to squint at the ingredients on the label. I wasn’t surprised to see that it was made with olive oil instead of the usual vegetable oil, and a mix of spices, including cumin, when I researched the brand out of curiosity, the story just got better.

Lellouche works with only the highest quality peppers–habanero, chili bird’s eye et bakhlouti fumé, and hand-peeled garlic from Lautrec. The spices he adds to his harissa are ground daily to assure as much vivacity of taste as possible, and he uses only first-rate olive oil, too. And just F.Y.I, the word harissa derives from the Arab verb

What all of this means is that Have Tada Pilpelta is the caviar of harissa and completely lives up its puckish name. In the Talmud, there’s a dictum that goes “Better one spicy pepper than a whole basket of pumpkins.” So from the Aramic language, this explains the name of this wonderful line of harissa-based products, Tava (it’s better to have) Hada (a single) Pilpelta (pepper). Other products in the line include harissa-seasoned poutargue, cashews, oil and the other condiment that I’ve become addicted to, a bright mixture of minced pickled lemon and harissa that will see the gray off of any winter day and turn a steamed cod or grouper filet into a magnificent meal.

For now, Tava Hada Pilpelta products are only available in France at a variety of retailers in Marseilles, Paris, and elsewhere, but you can also order them online at www.harissa-thp.fr

And though it seems unlikely that the Fancy Food Fair in New York City will be held this year, if I were a North American importer specializing in highest quality off-beat condiments, I’d jump on this company in a heartbeat.